Note: This article originally appeared on my Film-to-Film site, which was devoted to comparing two different versions of the same story. I decided to discontinue this site because the amount of work that went into each article was well beyond the response they received from the public. I’m republishing this one here as a taste of what that site was like. The others article from Film-to-Film (along with this one) will appear in my book of film essays, which I’m hoping to have published later this year. You can see my other work on the Amazon author’s page.

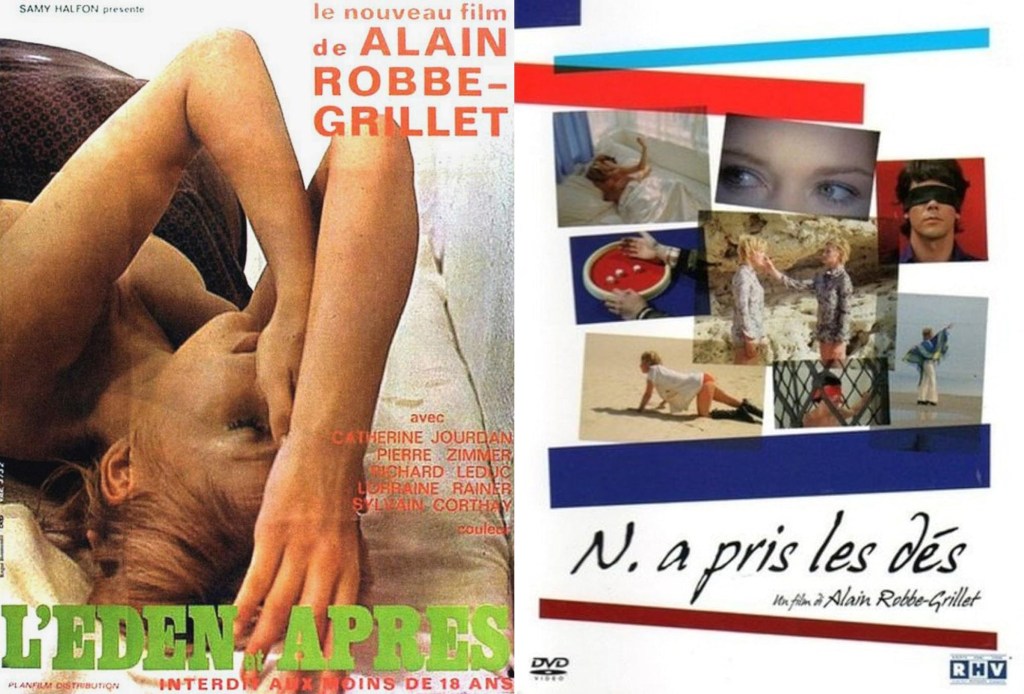

I’m going to do something completely different this time around. While the main function of this website is to compare to films made from the same story, this time I’m going to talk about two movies made not from the same story, but from the same film. The first film, Eden and After (L’Eden et après), was made in 1970 and was a nominee for best picture at the Berlin Film Festival (more on that later). The second film was N. Took the Dice (N. a pris les dés…) and was made for television two years later. Both films follow the misadventures of a young blonde woman in Tunisia and at a cafe called Eden, and some of the action in both films centers around a small blue-and-white painting and a pair of men who may or may not be the same person.

If this sounds mind-bendingly convoluted, that’s because these are Alain Robbe-Grillet films and Robbe-Grillet specialized in just that sort of thing. Robbe-Grillet had an odd career. He got his start as an agronomist, but in 1953 he tried his hand at writing novels and found he liked that better than improving crop yields. His first book, A Regicide (Un Régicide), was rejected, but his second book The Erasers (Les Gommes), went on to receive the Prix Fénéon the year after it was published. Over the next few years, he wrote three more books, but was still frustrated. He had visual images in his head and he wanted to show these rather than describe them.

Meanwhile, filmmaker Alain Resnais was looking for a way to make films that would redefine French filmmaking in the same way that writers like Samuel Beckett, Marguerite Duras, James Joyce, and Robbe-Grillet were redefining literature. He hired Duras to write the screenplay for Hiroshima mon amour, and then turned to Robbe-Grillet for his next film: Last Year at Marienbad ( L’Année dernière à Marienbad).

Before we go any further, I should mention that if you are allergic to French art films, you should stop reading right now. Robbe-Grillet is the poster child for this sub-genre. His films are both visually stunning and puzzling. Although Last Year at Marienbad was directed by someone else, it shows Alain Robbe-Grillet’s narrative approach in full effect. The story centers around three people—two men and a woman—who meet up at a posh hotel (actually the Nymphenburg Palace in Germany) and reminisce about events that happened the previous year in Marienbad. All three of them (they are never named) had been at a hotel in Marienbad the previous year and one of the men claims that the woman said she’d run away with him if he waited a year. The woman denies this. The other man (who may or may not be the man’s husband, likes to demonstrate his intellectual superiority by playing NIM, a matchstick game that you can almost always win once you know the strategy). The man may be misinterpreting things, while the woman might simply be lying. In any case, the remembrances from the previous year in Marienbad all come from unreliable narrators. Last Year at Marienbad was both a hit and a source of irritation for anyone who equates abstruseness with pretension. Indeed, the film has become the poster child for incomprehensible French art films.

Although Robbe-Grillet liked working with Resnais because—unlike nearly every other director on the planet—Resnais allowed Robbe-Grillet to dictate the scene compositions. Even so, Robbe-Grillet found things in Last Year at Marienbad didn’t jibe with his own internal images and decided that the only way to turn his ideas into films correctly was if he directed his own films.

His first three films—L’immortelle, Trans-Europ-Express, and The Man Who Lies (L’homme qui ment)—were shot in black-and-white. But by 1970, virtually no movies outside of the Eastern Bloc countries were shot in black-and-white anymore. Robbe-Grillet liked color, and would have shot The Man Who Lies in color except for one thing: Much of the action takes place in a forest and Robbe-Grillet hated Eastmancolor’s green. For his first color film he wanted to make a movie that avoided green as much as possible. That film was Eden and After.

Eden and After

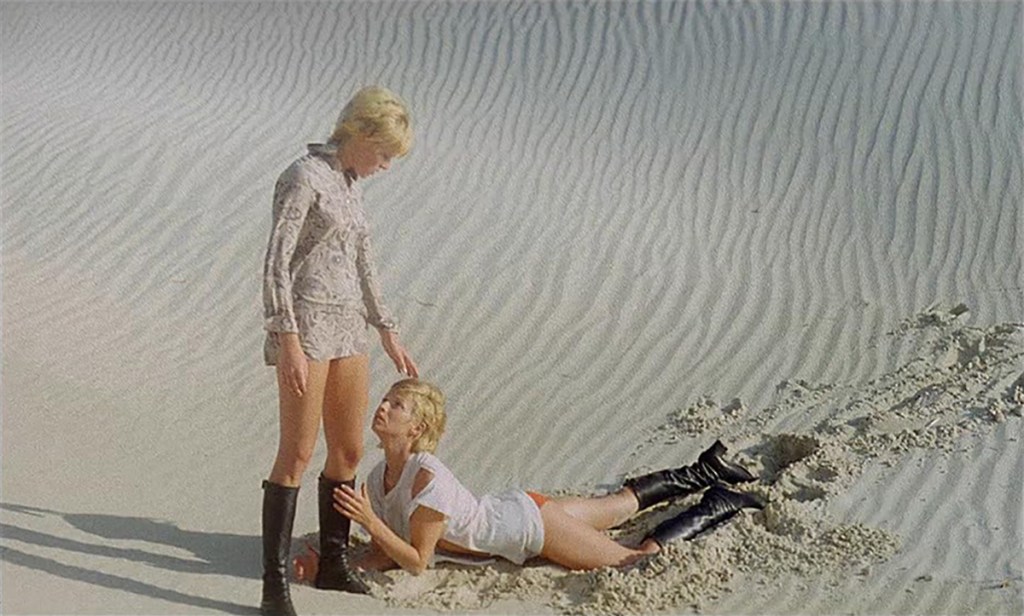

Eden and After follows the shenanigans of a group of college students who, bored with life, spend their spare time playacting in scenarios involving rape, poisoning, and Russian roulette. They do this at a place called the Eden Café, whose interior is divided into multiple rooms by glass panels painted with patterns that resemble the work of Piet Mondrian. The main character in the movie is Violette (Catherine Jourdan), a young blonde, whose Pixie-cut hairstyle, micromini dresses, and black knee-high boots make her look like she stepped out of a sixties Carnaby Street fashion shoot.

Things at the café are going along as usual until a stranger named Duchemin (Pierre Zimmer) shows up and offers the students something he calls “fear powder.” What follows is hallucinogenic flashes forward involving a stolen painting, a creepy factory, and women blindfolded in cages.1 Violette goes to Tunisia where she meets an artist named “Dutchman,” who looks like Duchemin and is played by the same person (it’s no accident that the name Duchemin resembles Duchamp—Grillet cites Duchamp, Mondrian, and Klee as his main inspirations for the visuals in the film). Violette also meets her own Doppelganger, but who is played by somebody else (Eva Luther).

Rather than use a formal script, Robbe-Grillet wanted to make the movie without a script. For this reason, he chose to use a largely unknown cast, figuring that more experienced actors would balk at doing a movie without a shooting script. At the time, Robbe-Grillet was fascinated with modern music composers. Rather than a script, Robbe-Grillet used twelve themes in imitation of Arnold Schoenberg’s twelve-tone scale. These were assorted into ten combinations of two or more themes, but even Robbe-Grillet is hard pressed to tell us what those series and themes were. Before each scene, the cast and cinematographer, after being presented with a theme, would discuss what they were going to do and say, and how it would be filmed.

Eden and After was up for a Golden Bear award at the 20th Berlin International Film Festival, but we’ll never know if it would have won. The awards were called off because director George Stevens took offense to Michael Verhoeven’s o.k., a film about the rape and murder of a Vietnamese woman by a group of American soldiers in Vietnam. He accused the film of being “anti-American>” Never mind the fact that the events portrayed in film actually happened.2

N. Took the Dice

Two years after Eden and After was released, Robbe-Grillet made N. Took the Dice. In French, the name of the second film (N. a pris les dés…) is `supposed to be an anagram of the name of the first film (L’Eden et après), but I guess nobody bothered to check this because it’s not. This time around, the story revolves less around Catherine Jourdan than Richard Leduc, who played Marc-Antoine in the first film. He is the narrator in this film (the “N” in the title), and he sits at a table and tosses three dice in a rolling tray and arranges them according to his whims. Where Violette’s doppelganger doesn’t appear until the end of the first film, she is almost the first thing you see in N. Took the Dice. Violette is now called Eve, although the narrator isn’t sure if this is actually her name. In interviews, Robbe-Grillet simply refers to her as “elle” (she/her).

While the first film has a linear story with occasional flashbacks and flashforwards, the second is a different matter. Robbe-Grillet took all the footage he shot during the making of Eden and After and constructed a completely different film. As previously mentioned, Robbe-Grillet was fascinated with modern composers and the techniques they used. The first film followed the serialism of Schoenberg and the twelve-tone scale, but for the second film he wanted to move even further into experimental realms with the addition of chance, and, in particular, aleatory construction. Aleatory is simply a ten dollar word for chance. More literally, it means chance determined by tossing dice (alea is the Latin word for dice). Robbe-Grillet wanted to do the same thing with film. He wanted to see if he could make a coherent second film out of the footage he shot for the first film. It turns out he not only could. But it would, if anything, make for a more coherent film with a more intriguing story.

Knowing ahead of time that he was going to be making a second movie from the footage, he made sure the cinematographer shot plenty of extra footage. He had hoped to use completely different footage for both films, but time and economic pressures prevented this. He ended up shooting some new footage, and threw out most of the sound and dialogue from the first film to create a new story. For this reason, we rarely see anyone actually speaking and most conversations focus on the listener instead of the speaker, à la Godard. Robbe-Grillet demonstrates that, in spite of the added element of chance, he is still the director and he can still manipulate things. Whenever N. rolls the dice, he then rearranges them as he sees fit. Chance, perhaps, but not without some control over the results.

N. Took the Dice was not released in cinemas but was shown on television first. Television is referenced throughout, and by the end of the movie, the story has taken on characteristics of a game show. After discovering the body of the Dutchman/Duchemin in the water, Eve goes through his pockets and discovers a postcard labeled “TV Games” (les jeaux Télévisés) that reads: “Bravo! You’ve won a washing machine!” (Bravo! Vous avez gagné une machine à laver!). The narrator points out the ridiculousness of this resolution but cautions the viewer that any meaning found here comes from the viewer’s own interpretations. Robbe-Grillet, after all, merely followed the dice.

In the Final Analysis…

This is the subsection where I would usually compare the two movies to see which one was better, which one was truer to the original story (when applicable), and which one was more creative. None of these criteria have much meaning here. Robbe-Grillet was not working with a traditional narrative process for either film, and he had plans to make the second film while he was making the first. N. Took the Dice is a remake of Eden and After in the sense that it uses the physical material of the first film, but the narrative is completely different. The painting, the desert, the Eden Café are all still there, but their meaning and locations have changed. It’s closer to a cut-up, but unlike most of those (such as Burroughs’ Novatrilogy) the intent of the original story has also been removed.

If I had to choose, I’d say N. Took the Dice is the better of the two movies. Robbe-Grillet (or, at least, the narrator in the movie) is being a little disingenuous when he says that any meaning to the story is the result of the viewer’s imagination. Robbe-Grillet clearly thought this one out carefully. While the first film takes place in two separate locations—Tunisia and Czechoslovakia—the second film doesn’t have this luxury. Every moment is right here, right now, creating a larger puzzle and a more interesting environment.

While I know these films are not for everyone, I love both of them and can see why David Lynch is a fan of Robbe-Grillet’s work. There seems to be a similar approach to narratives in Lynch’s films, particularly with films such as Lost Highway and Inland Empire. Neither director likes to explain too much. As the narrator says at the end of N. Took the Dice: “It’s the journey that matters, not the goal.”

IMDb page for Eden and After

IMDb page for N. Took the Dice

1. One of the knocks on Robbe-Grillet’s films in these puritanical times is his use of S&M imagery. Themes on this subject run throughout his films. Not surprisingly, his wife Catherine Robbe-Grillet defined herself as a “lifestyle dominatrix.” Under the pseudonym Jean de Berg, Ms. Robbe-Grillet wrote The Image, now considered a classic of BDSM literature. In 1975, the book was was made into a movie by Radley Metzger and was renamed for some markets as The Punishment of Anne.

2. Brian De Palma made his own version of the story in 1989 with Casualties of War, which is based directly on David Lang’s New Yorker article. It starred Michael J. Fox and received a lot more accolades and attention than the Verhoeven film. (I might do a film-to-film on this at some point).

© Jim Morton and Pop Void Publications, 2024. Unauthorized use and/or duplication of this material without express and written permission from this site’s author and/or owner is strictly prohibited. Excerpts and links may be used, provided that full and clear credit is given to Jim Morton.

Leave a comment