The Juvenile Delinquent Films of Germany

In March of 1955, a film titled Blackboard Jungle opened to the raucous strains of Bill Haley’s “Rock Around the Clock” and blew moviegoers out of their seats. The film was a hit with teenagers and led to feeding frenzy in Hollywood to make more films about juvenile delinquents (JD films). These films had their roots in film noir, with crime-based stories about young people who were either misunderstood or downright rotten. The protagonists were morally conflicted, and their crisis points came at the hands of others who were either trying to reform them or lead them to perdition.

Blackboard Jungle, and to some extent its predecessor The Wild One, started a global trend for films about disaffected teenagers. In Britain, Beat Girl bopped into theaters with an excellent John Barry soundtrack; In France, François Truffaut got his career rolling with The 400 Blows; and in Japan, Koreyoshi Kurahara’s The Warped Ones outdid all the others for shock value. Each country brought its own cultural perspectives to the stories. Being a juvenile delinquent in America was a very different thing from being a juvenile delinquent in Europe or Asia. Nowhere was this truer than in Germany.

In the 1950s, Germany was still divided into two politically incompatible countries. East Germany was established from the post-war Soviet sector, and was attempting to follow Russia’s lead with a version of communism that had less to do with Marx than Stalin. Meanwhile, West Germany, which was created from the Allied sectors, modeled itself after U.S. federalism. In West Germany, all things American were popular. This was thanks in large part to the 250,000 American troops stationed there during the Cold War. The American influence included everything from music and fashions, to the prevalent attitude toward older people. Inevitably, a certain percentage of German teens identified with American juvenile delinquents. Germans didn’t call them delinquents, though; they called them Halbstarken.

Halbstark is a word that doesn’t translate into English in any meaningful way. Literally, it means “half-strong” and suggests someone who is tough, but not as tough as they think. The negative connotations were weaker than “delinquent,” and German kids didn’t mind being considered Halbstarken. A band called “Die Yankees” even had a hit song in Germany called “Halbstark.” West German kids took to this new counterculture like bees to flowers.

The focal point of this movement was not Elvis Presley, but Bill Haley and the Comets. The chubby, bow-tie-wearing Bill Haley seemed like an unlikely model for young thugs, but his song in Blackboard Jungle made him the poster child for German juvenile delinquents. Exploitation producer Sam Katzman saw the potential box office for a jukebox movie that featured Bill Haley and his band. He quickly cobbled together a script and Rock Around the Clock was filmed in January of 1956 for release in drive-ins and grindhouses two months later. When Rock Around the Clock played in Britain and Germany, kids tore up the cinemas. In Bremen, water cannons were used to quell the rioting after the delinquents in the movie house took their rampage into the streets. When Bill Haley played at the Berlin Sportpalast in 1958, a full-blown riot ensued, with Haley and the band fleeing the venue before their set was finished.

One of the best German juvenile delinquent films from that period came from West Germany. Its German title is Die Halbstarken. The film was picked up for American release by Distributors Corporation of America (DCA) and given the much better title of Teenage Wolfpack. DCA specialized in providing films for drive-ins and grindhouses and is most famous today as the distributor of Ed Wood Jr.’s Plan Nine from Outer Space. They cut the film to remove some brief nudity and dubbed the film (badly) into English. To disguise its German roots, the name of the film’s star, Horst Buchholz, was changed to Henry Bookholt. It would be a few years before Buchholz made a name for himself in America playing the hot-headed Chico in The Magnificent Seven, but in Germany, Bucholz’s star was already on the rise and the movie solidified his fame.

Teenage Wolfpack follows the misadventures of Freddy (Horst Buchholz), a young tough in black leather pants who masterminds the robbery of a postal truck. For all his outward bravado, Freddy is a softie at heart whose real goal is to marry his girlfriend Sissy (Karin Baal) and raise a family. He is half-strong in every sense—part gang leader, part romantic dreamer.

Sissy is another matter entirely. She is a femme fatale of the first order—beautiful, seductive, and ruthless. She’s less interested in marriage than she is in money. Freddy’s love for her drives him to take greater and greater chances. Sissy, on the other hand, treats him like a possession and gets jealous when he starts spending time with his brother. She is perfectly willing to betray him to get her way and is not above resorting to murder. Karin Baal’s portrayal of Sissy is spot-on, and it was her first film role. She would return to juvenile delinquency in Judge and Juvenile (Der Jugendrichter) and Und sowas nennt sich Leben, and then go on to play more adult characters in films such as Rosemary (Das Mädchen Rosemarie), Dead Eyes of London (Die toten Augen von London), and Lola.

In response to Teenage Wolfpack, DEFA (the state-owned film production company in East Germany) released Berlin – Schönhauser Corner (Berlin – Ecke Schönhauser). As with other juvenile delinquent films, the teens in Berlin – Schönhauser Corner were irresponsible and just wanted to have fun. Like James Dean in Rebel Without a Cause, their relationships with their parents left something to be desired. The leader of the group is Dieter (Ekkehard Schall), whose parents died during WWII. He lives with his strait-laced brother who also happens to be a cop in the Volkspolizei. Dieter has the least to rebel against, but he likes the free-ranging anarchy of the street corner. In contrast, the parents of Karl-Heinz (Harry Engel) are alive and rich and are not happy about being stuck in East Germany. They’d leave, but they own their house and don’t want to part with it. It’s clear by his use of money to get what he wants that this fruit didn’t fall from the tree. If there’s a villain in the film, it’s Karl-Heinz. The patsy in the group is Kohle (Ernst-Georg Schwill), who, like Sal Mineo’s Plato in Rebel Without a Cause, just wants to be respected as part of the gang. Kohle’s home life is miserable. His father is a drunk who settles every argument without violence, forcing Kohle to escape to the streets.

After a fight with Karl-Heinz, Dieter and Kohle flee to West Berlin, and are put in a reception center that has all the characteristics of a cult compound. Eventually Dieter sneaks back to East Germany, happy to be safe again in the GDR. Kohle, afraid of being shipped to the West without Dieter, feigns sickness, which leads to a catastrophe.

The most striking portrayal in the film comes from Ilse Pagé as Angela, a bored teenager in a turtleneck, bullet bra, and Capri pants. Here’s where the comparisons to Rebel Without a Cause start to break down. Angela is nothing like Natalie Wood’s squeaky-clean Judy. She’s raunchy! Unlike the rest of the cast, Pagé was a West German. Reportedly, director Gerhard Klein couldn’t find an East German actress who exuded the sultry loucheness he was looking for. It was Pagé’s first film role and the start of a long career in films that includes memorable parts in Volker Schlöndorff’s The Tin Drum and Helmut Käutner’s Black Gravel.

Other juvenile delinquent films were made in both West and East Germany, but nothing on the scale of the flood of JD films that came out of the United States. The Austrian director Georg Tressler, who got his start with Teenage Wolfpack, went on to make a few more films centered around the travails of young people. These films include Under 18 (Noch minderjährig), Last Stop Love (Endstation Liebe), and Confessions of a Sixteen-Year-Old (Geständnis einer Sechzehnjährigen) which features songs by the German pop group Die Bambis Cliff Richards wanna-be Billy Sanders.

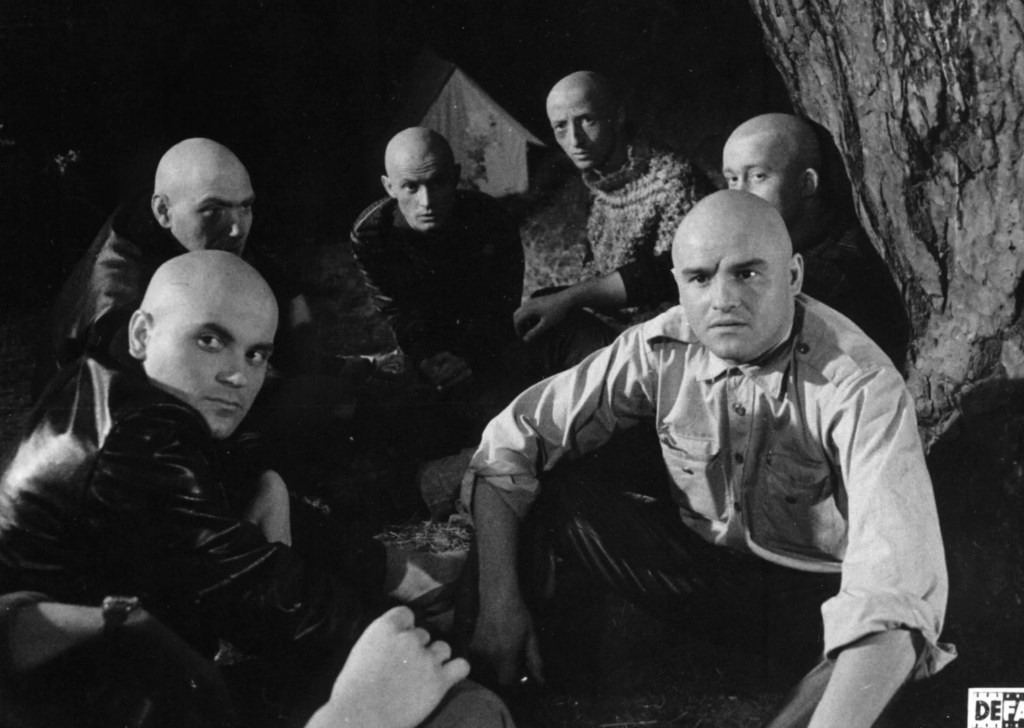

As we moved into the sixties, the delinquents also moved into adulthood. The market for films about surly teenagers dwindled. Juvenile delinquents were replaced with criminal thugs in films such as These are the Damned, Kitten with a Whip, and Lady in a Cage. The sixties also saw the start of the biker genre. One of the earliest examples of this genre came from East Germany with The Bald-Headed Gang (Die Glatzkopfbande). This film follows the misadventures of a motorcycle gang whose members shave their heads because their leader is a fan of Yul Brynner. Like The Wild One, the film is based on an actual event and like the Marlon Brando film, the real event was far less sensational than how it was portrayed. The Bald-Headed Gang was filmed after the Berlin Wall went up, and part of its message was that, if not for the Wall, these criminals would have escaped justice.

In West Germany, the taste for films about disaffected youths dried up long before the market for them in the U.S. did. By the mid-sixties, the German film market had shifted to the more adult themes reflected in the popular crime films called Krimis—but that’s another story for another time.

Leave a comment