The Final Days of the GDR

This is a heavily abridged version of Chapter Fifteen in my book, Movies Behind the Wall. This version contains only the text that deals with the historical events of 1988 and ’89, and not the movies that were released by East Germany’s film production company DEFA during those years.

By 1988, things were moving fast all over Eastern Europe. Gorbachev promised more government transparency, democratic reforms, and less interference in the politics of other countries. He made good on the last promise when, in September of 1988, the Soviet Union did nothing to prevent the election of Solidarity party member Tadeusz Mazowiecki as the first non-communist prime minister in Poland. This went contrary to Brezhnev’s 1968 doctrine, which stated that any shifts away from socialism to capitalism represented a threat to all the countries in the Eastern Bloc and must be prevented. On October 25, 1989 the spokesman for the Soviet foreign ministry Gennadi Gerasimov let it be known that the Brezhnev Doctrine was no longer in effect, replaced by a more laissez faire approach, which he jokingly referred to as the “Sinatra Doctrine” in reference to Sinatra’s hit, “My Way.” Perhaps someone should have pointed out to him that the first line in that song is: “And now, the end is near.”

Faced with a rapidly changing world, the ossified old men who headed the SED preferred to put their hands over their eyes and sing “Auf Ruinen” as loud as they could rather than face the fact that the events of the world were well out of their control. They increased surveillance, enlisting as many as 200,000 people to spy on their neighbors, and came down on anyone who made the slightest sign of protest. Now, their most important ally, the Soviet Union, had let them know they weren’t going to back them in this endeavor.

The reasonable thing to have done would have been to acknowledge the sorry state of things and start adopting the changes that Gorbachev was promoting, but Honecker and his cronies were beyond reason. They came from the old school of Soviet communism that brooked no compromise. It was this same stubborn refusal to compromise on the part of the communists that lost the Republicans the Spanish Civil War and helped put Hitler in power in Germany. Honecker responded to the dissolution of the Brezhnev Doctrine by denouncing Gorbachev. Perhaps he thought there’d be enough dissatisfaction in the Soviet politburo to lead to a coup against Gorbachev, but this wasn’t the case. Instead, members of Honecker’s own party started to plot to oust him.

DEFA chugged on, delivering quality films on a variety of topics, despite things falling apart around them. The last few months of the state’s existence would still provide a few classic films for the East German public, including The Actress (Die Schauspielerin), whisper & SHOUT (flüstern & SCHREIEN), Winter Adé, Just Married (Grüne Hochzeit), and Coming Out—which is still one of the most candid movies on gay love ever made.

Honecker Reiterates His Position

Lest anyone think he was losing his grip on things, Erich Honecker publicly let if be known how he felt about the Wall he helped build. Speaking at a meeting of the Thomas Müntzer Committee, he reiterated his position: “The Berlin Wall,” he said, “will exist in 50 or even 100 years if its reason for existing is not addressed.” He was right, of course, he just didn’t comprehend that he was the main reason it still existed at all.

The Last Casualties

On February 6, 1989, 20-year-old Chris Gueffroy and his friend Christian Gaudian decided to try and escape to West Berlin across the heavily guarded East Berlin border. The two were under the mistaken impression that the Schießbefehl—the long-standing order for East German border guards to fire on people trying to climb the wall or cross the border—had been rescinded. They were about to find out the hard way just how wrong they were. After getting past the first few hurdles, the duo was spotted trying to climb the metal fence that bordered the Britz canal. The border guards let loose with a volley of shots. Gueffroy was hit ten times and died on the spot. Gaudian managed to survive and was promptly arrested and sent to the prison hospital and then a cell.

The border police who fired on Gueffroy and Gaudian were given medals and bonuses for their actions. After reunification, the tables would turn. Gaudian would be pardoned, and the guards would find themselves charged with murder. Most were acquitted. The guard who fired the fatal bullet was given a three-and-a-half-year sentence, which was later reduced to parole. The infamous Schießbefehl was repealed in April. Two months too late for Chris Gueffroy.

Gueffroy was the last man shot trying to climb the Wall, but he wouldn’t be the last casualty of the barrier. A month after Gueffroy’s fatal attempt, in the early morning hours of March 8, 1988, a man named Winfried Freudenberg from Berlin ‘s Zehlondorf area started filling a homemade balloon with natural gas for the express purpose of flying him and his wife Sabine over the Berlin Wall. The balloon was almost ready when the police arrived, notified by a local passer-by who saw the balloon. Feeling that the partially inflated balloon would not hold the weight of both people, Sabine convinced Winfried to go it alone and leave her behind. Fearing that the gas would explode, the police decided not to fire on the rising balloon. What happened next is unclear. Winfried Freudenberg’s body was found in a garden in the Zehlendorf district in West Berlin, nearly every bone in his body was broken, indicating he fell from a great height. The balloon eventually ended up in a tree along the Potsdamer Chaussee near Spanische Allee. Sabine Freudenberg was arrested when she returned to her house that morning, and the Stasi began investigation of her and all the friends and relatives of the Freudenberg’s. Sabine was given a three-year suspended sentence, then was “amnestied” on October 27, 1989.

Candles in Leipzig

In Leipzig, pastor Christian Führer started holding a weekly “prayer for peace” (Friedensgebet) at the Nikolaikirche every Monday night, starting in 1982. Every week, the congregation grew, until by 1989 it included a wide variety of disgruntled Leipzigers, along with a few Stasi sent to watch over things. On March 13, 1989, during the Leipzig Spring Fair, several hundred people left the church and formed a protest in the streets, shouting “We want out!” The police showed up and started arresting people. It looked like they had things under control, but they were mistaken. The protests got smaller, but then began to grow. By the end of October, an estimated 320,000 people were protesting in the streets of Leipzig, and similar protests were springing up everywhere.

May Day 1989

There is no more important holiday among socialists and communists than May 1st, known variously as May Day and Workers’ Day. The choice of May 1st was in acknowledgement of an event that happened in Chicago when a protest at Haymarket Square turned violent. What were they protesting? They wanted an eight-hour workday. When it came time for the United States to create a celebration for workers, rather than acknowledge the protests at Haymarket Square, they chose the first Monday in September and called it Labor Day, in an attempt to avoid any association with socialism. While the rest of the world celebrates the efforts of American workers to get a fair wage and stop working ridiculous hours, here in America we pretend it didn’t happen.

For the Soviet Union, May Day was a chance to display their might with row after row tanks and troops marching in front of the Kremlin. East Germany held a parade along similar lines, with rows of Volkspolizei marching before Erich Honecker. May 1st, 1989, was a little more fractious than usual, with simultaneous parades and protests. In East Berlin, 700,000 people participated in a four-and-a-half hour peace protest. Similar things were happening all over the country, but Honecker ignored them. He would have liked to call in the Soviet troops, but the Soviets were no longer interested in propping up the SED’s rotting cadaver. In effect, Gorbachev told Honecker that it was his mess. He’d have to clean it up.

Hungary Removes Its Fences

On February 11, 1989, the Hungarian Socialist Workers’ Party—Hungary’s equivalent to East Germany’s SED party, agreed to give up its monopoly in favor of multi-party elections. They also agreed to dismantle the barbed-wire and electronic alarm fences along their border. On May 2nd, that process began. Since Hungary was one of the countries that East Germans could travel to with relatively few restrictions, thousands of East Germans headed to Hungary. At this point, the border was still not open in spite of the absence of fences, as some unfortunate East Germans discovered when he tried to flee to Austria.

The People Vote

On May 7th, 1989, the SED made a big show of having a free and open election to determine the future government in East Germany. Since the “National Front” (a party bloc consisting primarily of SED members) was the only choice, voting consisting of doing one of two things: You could either fold up your ballot and put it in the box, or cross out the choices first, making it readily apparent to the Stasi officers patrolling the voting booths who voted yes and who voted no. That should have been enough to ensure most people would vote the way the party wanted, but, never one for half measures, the SED engaged in voter fraud as well. When the results came back 98.85 percent in favor of the current government, it didn’t take a mind reader to recognize that something was fishy. In the West, it was a source of outrage. In the East it was a source of cynical humor. It changed nothing, but further sparked the flames of discontent in the GDR.

The Summer of Our Discontent

After weeks of protest in Tiananmen Square in Beijing, China, the military came in on June 4, 1989, a put an end to the protests, an act that the leaders in East Germany heartily endorsed. Meanwhile, next door in Poland, the Solidarity party won 92 out of 100 seats in the Polish senate, effectively knocking the communist party out of government. Honecker may have sided with China, but China was far away. Poland was right next door.

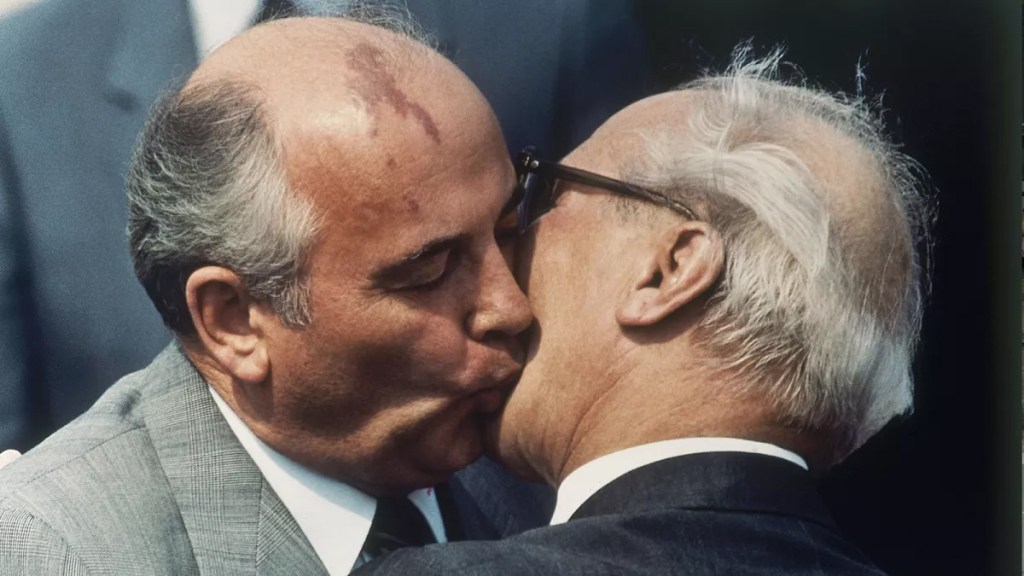

Adding insult to injury, Gorbachev traveled to West Berlin and signed an agreement with Helmut Kohl, stating that every state has the right to choose its form of government and every citizen has the right to choose that form of government. Honecker criticized the agreement at the next meeting of the Central Committee, but said, somewhat jokingly, “At least they acknowledge that Erich Honecker and the GDR exist.”

Every month, more and more people were requesting exit visas to get out of East Germany. By mid-summer, the number surpasses 10,000 a month, come August the number was up to 20,000. Many were granted the visas, partly to get rid of them. But the numbers were becoming too much to bear. Suddenly the Berlin Wall, designed to strengthen the border and end the Republikflucht, was becoming as big a nuisance as the problem it was intended to fix.

Hungary Opens Its Borders

Hungary wasn’t keen on the idea of policing its borders just to keep East Germany happy. At the end of August, Hungarian Foreign Minister Gyula Horn traveled to East Berlin to meet with East Germany’s minister of foreign affairs Oskar Fischer, the acting spokesperson for the SED Günter Mittag, and the ailing Erich Honecker. Horn was there to tell the Germans that on September 11th, Hungary would be opening its borders to East German refugees. As you might imagine, Fischer, Mittag, and Honecker weren’t happy.

East Germans had already been traveling to Hungary in droves, along with many Stasi members, sent to try and convince people to return to the GDR. For the most part, their requests, forceful or not, fell on deaf ears. Then on the evening of September 11, as promised, the border between Austria and Hungary was opened. What followed was a stampede of East Germans, running for Austria with all their might, dragging along their children and anything they could carry in their arms. Hundreds of Trabis were left on the streets near the Hungarian/Austrian border; many with their keys still in them.

In response to the event, the SED stopped all travel to Hungary, so East Germans started heading to the West German embassies in Poland and Czechoslovakia. Eventually, the embassies had to close due to overcrowding. By the end of September, 33,255 East Germans had fled for the West, with only a third of them officially approved. On October 4, 8,270 East Germans were loaded onto a train in Prague that took them to West Germany. It was an exciting journey. The train was stopped at the Polish border, and several times more in East Germany. With each stop the passengers held their breath, fearing their next stop would be an East German prison. The train had to pass through the stations in Dresden and Karl-Marx Stadt (Chemnitz), where the police used force to keep the crowds from approaching the train

Things were spiraling out of control and would only get worse from here on out.

Gorby, Help Us!

Honecker finally broke his silence, sending a telegram to the SED ministers telling them that the only way to deal with these protests and “provocations” was to nip them in the bud. The police start to crackdown on the Monday night peace demonstrators in Leipzig, who had taken to shouting, “Wir wollen raus!” (We want out!). The border between Czechoslovakia and East Germany was closed. Step by step, the East German government was no longer simply walling itself off from the West, but from the rest of the world as well.

When Gorbachev arrived for East Germany’s 40th anniversary celebration, he was met with shouts of “Gorby! Save Us!” from the crowd. When he tried to discuss East Germany’s financial and political problems, Honecker trotted out the same old baloney about how well East Germany was doing. Gorbachev listened slack-jawed. Does this man think I’m an idiot? He wondered. In an interview later, he cautioned Honecker and his crowd that dangers await those who did not respond to the world around them. Some of the members of the Central Committee began to realize that they couldn’t continue down the dead-end path that Honecker has set for them.

Auf Wiedersehen Herr Honecker

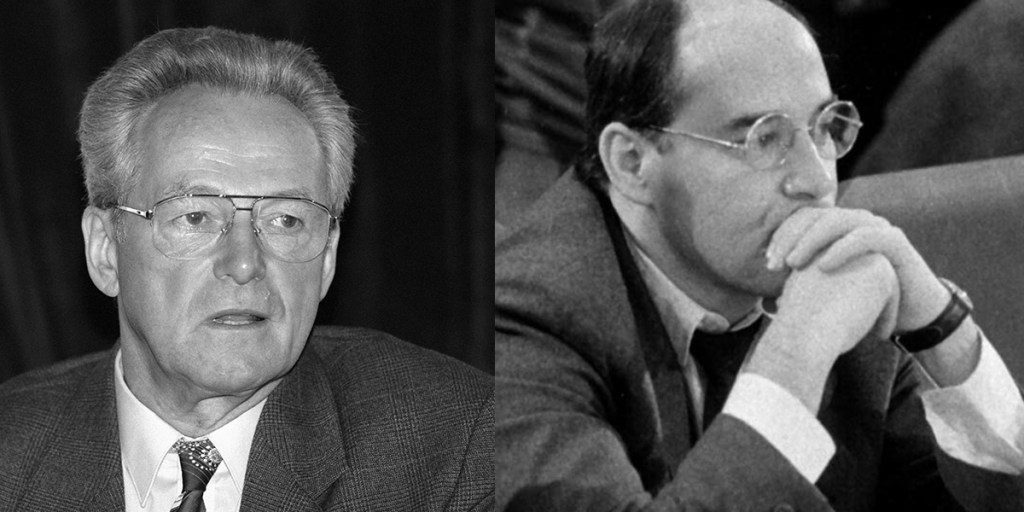

An emergency meeting of the SED Politburo was held to discuss the rapidly deteriorating situation in the country. While some petitioned for change, and even Mielke acknowledged the problem of trying to police everyone, Honecker stuck by his guns, continuing to trot out the party line and threaten to punish those who opposed it. A week later, a vote was taken on whether or not to replace Honecker. When everyone raised their hands, Honecker sat stunned for a second, then raised his hand, staying true to his communist belief in unanimity. Honecker was replaced with Egon Krenz, a party official who had made a career of not rocking the boat. On October 18th it was announced that Honecker was retiring “for health reasons.”

The Alexanderplatz Demonstration

At this point in East Germany, there wasn’t much Chairman Egon Krenz could do to save that ship. Truth be told, he wasn’t the man to do it anyway. By the end of October, nearly 60,000 had fled the GDR. People were pouring out of the country, most without official permission. The more the government tried to restrict travel, the worse it got. Slowly, they started to lift travel restrictions in hopes that it would stem this new Republikflucht. Restriction on traveling to Czechoslovakia were lifted, but the end result was hundreds of people streaming into Czechoslovakia again.

Public reactions were coming too fast for the East German government to process, and the Soviets continued to turn a blind eye to the problems facing the GDR, On November 3rd, Krenz appeared on television to assure the public that things were going to change in the GDR and there was no need to get riled up. To prove this, he allowed what was, for all intents and purposes, a protest rally against the government.

The rally took place on Alexanderplatz on November 4. Perhaps the SED figured not many would show up and that they could control the message. They were wrong on both counts. Over a half million showed up, and all of the speakers who were there to defend the SED were shouted down when they spoke. This included Günter Schabowski—who had been given the unenviable task of being the government’s mouthpiece—and the notorious head of foreign security Markus Wolf. Both men were roundly booed. Other speakers included writers Christa Wolf, Christoph Hein, and Stefan Heym; stage and film actors Ulrich Mühe, Steffie Spira, Annekathrin Bürger, and Johanna Schall; and political activists Bärbel Bohley, Marianne Birthler, and Jens Reich.

To make matters worse for the SED, the entire event was broadcast on East German television. Now there was no question that people wanted change. Perhaps seeing the handwriting on the wall, several government officials quit their posts. No one wanted to be the last man standing.

Schabowski’s Press Conference

Everything came to a head on the evening of November 9, 1989. Günter Schabowski held one of his standard press conferences. This time on the agenda was a new regulation that would allow East Germans to travel to the West. The regulation had been hammered out just a few hours earlier. After the note was written, someone decided, probably wisely, that the regulation would take effect twenty-four hours later, giving the border police time to hammer out any kinks in the new policies, but nobody bothered to tell Schabowski this when they handed him the note. He dutifully read the note in a droning voice that suggested he wasn’t even listening to what he was saying. When asked when the regulation would take effect, Schabowski looked at both sides of the note and then uttered the sentence that changed the world: “As far as I know, it’s effectively immediately” (“Das tritt nach meiner Kenntnis… ist das sofort, unverzüglich”).

Within the hour, the border crossings were choked with people demanding to be let across. The border police, who had heard nothing about this new policy, refused, and the crowds started to become restless. Panicking, they called their superiors, who, in turn, called their superiors. Some border guards were told to stamp the passports to indicate that the people going to the West would not be let back into the country. Others were told to cool their jets until someone could come up with a definitive answer to the question. A reporter on the East German TV news program Aktuellen Kamera announced the restriction that Schabowski was supposed to include, but by this time it’s too late. The crowds at the border were growing by the minute, and people were gathering on the other side as well.

The Wall Cracks

Eventually, the situation proved to be too much for the border guards. They had been instructed to let people through in small numbers, the higher-ups thinking that this valve approach would help alleviate the situation at the border, but it only made it worse. Finally, around eleven o’clock that evening, the guards gave up and people were allowed through en masse. People streamed across the border on foot and in their Trabants to the waiting crowds on the other side. That night was a celebration in West Berlin like no other. The East Germans were like kids in a candy store. By the morning, the stores of West Berlin were stripped of fruit, candy, and pornography.

The next few days proved to be especially stressful for the East German border guards, who still weren’t sure what they were supposed to do. The make things worse, people were scaling the Wall from the western side, and attacking it with sledgehammers. The whole situation was dissolving into chaos, but no one wanted to be the person that started World War III. West German Chancellor Helmut Kohl and SED General Secretary Egon Krenz began discussions. Krenz told Kohl that he saw the opening of the wall as a good start to a new sense of cooperation between East and West. What Kohl didn’t tell Krenz was that he had no intention of cooperating. He wanted nothing less than the total destruction of the GDR and all it stood for. Meanwhile, British Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher met with Mikhail Gorbachev to express her fear of a reunified Germany. As far as she was concerned Germany should stay split in half. The French prime minister François Mitterrand felt the same way but took a more Gallic attitude toward the situation—which is to say, he shrugged. He recognized that if President Bush and Gorbachev weren’t opposed to reunification, his vote wouldn’t count for much.

Krenz Cries Uncle

Finally, Krenz threw up his hands and walked away. Gregor Gysi was chosen to replace him as the new SED chairman, and Manfred Gerlach was named the Chairman of the State Council of the German Democratic Republic. These two were chosen for their pro-Gorbachev opinions. Perhaps the State Council was hoping that by getting back in the good graces of the Soviet Union they could stave off the inevitable, but it’s not called “the inevitable” for nothing. People started chipping away at the Berlin Wall, partly to bring it down, but partly to make money. That December, pieces of the Wall were one of the hottest selling Christmas items. Day and night, the streets of West Berlin along the Wall were filled with the constant sound of hammers tapping, leading to the appellation Mauerspechte (wall peckers) for the people chipping away at the Wall. The East German border guards stood by and looked confused. Some stayed drunk, and some sold parts of their uniforms to passers-by. At this point, the GDR was only pretending to be a country, but it would continue that charade for several more months.

Leave a comment